Freshman courses, students grapple with OBG system’s expansion

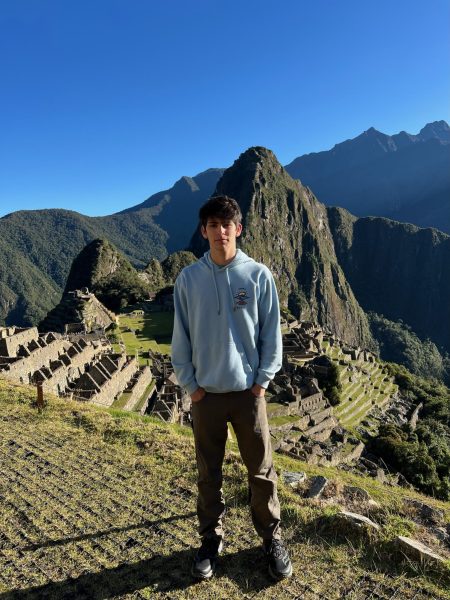

Karl Schmidt teaches a freshman physics class this fall. The Branson administration has expanded objectives-based grading to all freshman classes.

November 22, 2022

Objectives-based grading has commenced its second year at Branson in its expanded role as the school begins to solidify the rubric-focused grading system in all introductory courses.

Its future at Branson is still yet to be determined, but students are eager to express their praise as well as their concerns. OBG has been at Branson for four years in select courses, but only emerged from the science department last year and became a core part of all other freshman classes. Director of Studies and English teacher Jeff Symonds said OBG has found a home.

“I would say that we are more solidified in terms of our practice,” he said. “We now have oriented the program in those introductory-level, ninth grade courses. It’s much more in place and understood schoolwide.”

OBG, however, remains in its experimental phase as faculty members continue to assess how the progressive grading system is affecting student life.

“I don’t know if we’ll know if OBG is having the impact we want to have, which is, primarily, to help students see learning as the gateway to high performance until we’ve done it for a couple more years,” Symonds said.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic may have played a role in data regarding student performance. This makes it difficult to distinguish which changes can be accredited to OBG and which are simply a byproduct of the well-researched effects of the pandemic on motivation and learning.

“Students who came in last year and this year [were] really disadvantaged in comparison to previous years,” Symonds said. “Parsing out OBG’s impact and the pandemic’s impact on student performance is tricky.”

Sophomores and freshmen share mixed feelings about OBG. Reese Furhman has returned to Branson this year as a sophomore and reflected on her experience during freshman year.

“It kind of stressed perfection instead of proficiency, so it kind of, I feel, does the opposite of what it’s supposed to do,” she said. “You would get marked off as developing if you made one mistake. Something that would have been an A or an A- was considered to be on par with a B.”

Furhman and Simone Schachter, a freshman, said that, since OBG emphasizes growth and improvement, many teachers are inclined to give unfairly low scores right off the bat.

“Some teachers might want to start you off at a lower grade and, like, bring you up in a way to show that you’ve progressed, but if you had regular grades — percentage grades — then that would not be happening,” Schachter said. “I feel like it makes it less accurate.”

Sophomore students found that OBG during their freshman year was notably more forgiving. It encouraged students to delve into the material and reinforce their knowledge for the purpose of learning rather than scoring high on an assessment, especially since they knew they’d have another chance and would be able to forsake scores they weren’t proud of.

Objectives-based grading effectively changes the conversation from helping students satisfy a loosely representative cumulative points system to helping them achieve broader, overarching learning targets, Symonds said.

“OBG is a way to diagnose what you’re doing well and what you could do better, more immediately, when it’s working,” he said. “If it turns out that OBG is not [accomplishing] that after four or five years — I also hope we’re brave enough to revisit it — we don’t just keep it because we have it.”