Egyptian oppression described in the Bible. Babylonian exile and destruction of the First Temple. The Roman Empire’s dehumanization and forced diaspora of the Jewish people. Early Christian writings falsely accusing Jews of deicide — the killing of Jesus Christ.

The Crusades, where thousands of Jews were slaughtered in massacres across Europe. The first blood libel in England, baselessly accusing Jews of murdering Christian children for ritual purposes. The Inquisition and the mass expulsions of Jewish people from England, Spain, Portugal and Italy.

The ghettos that restricted Jewish life in 19th-century Europe, culminating in the systematic murder of over six million Jews during World War II called the Holocaust.

Antisemitism is not new. It has defined the almost 4,000 years of Jewish history.

Today, Jews make up less than 0.2 percent of the world’s population, according to Pew Research, yet are consistently one of the most targeted groups for hate crimes globally. A shocking 46 percent of adults worldwide harbor significant antisemitic beliefs, according to the Anti-Defamation League. And, as of the last couple of weeks, antisemitism exists not only abroad or in history books but here, at Branson.

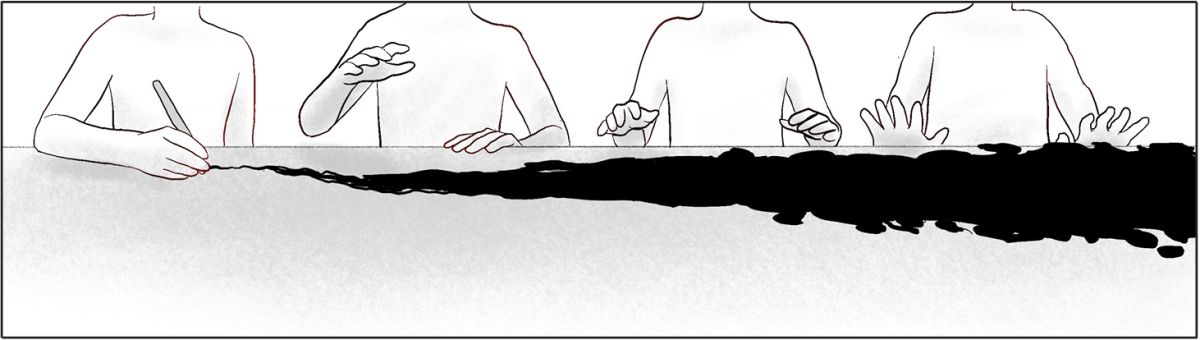

In April, several swastikas were found etched into the wooden Harkness tables in Study Hall, particularly in Study Hall 3. The symbols varied in size, with the largest being about one and a half inches in diameter. Some students noticed the antisemitic graffiti and transformed the swastikas into drawings of windows. Then someone re-etched the swastikas into multiple places on the table, including on top of the windows, some in red pen.

This was not a one-time lapse in judgment. It was deliberate, repeated and malicious. Every ninth-grader learned what the swastika was at Branson, and the murderous regime it represented, as part of the two-class-long coverage of the Holocaust in Modern World History.

The swastika is not just a symbol; it is a call for violence. Adopted by Adolf Hitler and his Nazi regime, the symbol comes from the the Sanskrit symbol for well-being or good fortune, but today it represents the ideology that led to the murder of millions, including Jewish people, Romani people, members of the LGBTQ+ community and other minorities who were viewed as non-Aryan civilians by the Nazis.

We commend the administration for taking this incident seriously. Assistant Head of School for Academics and Dean of Faculty Jeff Symonds made it clear in an email to the entire Branson community: “If you are the person responsible, I urge you to come forward and tell me so I can help you find a more appropriate place to go to school.” This response sends a clear message: There is no place for hate at Branson.

Equally powerful was the response from Dave Reiter, a math teacher and an adviser to Jew Crew, Branson’s Jewish affinity space. In an assembly, he shared, “To me, the swastika means that you want to kill me and my family.”

Throughout history, antisemitism has thrived in moments of uncertainty and crisis. When societies face political upheaval, economic collapse or social change, Jewish communities have often been scapegoated. One infamous example is “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a forged document that falsely claims Jews secretly conspire to control global events. Despite being thoroughly debunked, this lie continues to fuel hate to this day.

Antisemitism doesn’t spread because of facts; it spreads because it offers an easy target when people look for someone to blame. It mutates to fit the fears of each era, but its core, the dehumanization and vilification of Jews, stays the same.

Unfortunately, what happened at Branson reflects a broader nationwide trend: Antisemitism is becoming more mainstream. Tropes, caricatures and slurs are increasingly visible at protests, particularly in the wake of global conflict. Some protesters in the U.S. even cheered on the Oct. 7 massacre, as reported by the The New York Times. Antisemitic incidents jumped 360 percent after Oct. 7, according to the ADL. Though Israeli-Palestinian history is fraught with conflict and far too complicated for an editorial of this length, there is never an excuse for hating a group of people because of their identity.

Online, antisemitism thrives in comment sections, memes and anonymous accounts. Platforms such as TikTok, Instagram and X (formerly Twitter) allow their users to hide behind screens and pseudonyms, spreading hateful messages they would otherwise never say aloud. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue found a 5,000 percent increase in antisemitic YouTube comments in the days following Oct. 7.

Even here at Branson, casual antisemitic or racist jokes have become more commonplace. Regardless of intent, they perpetuate harmful and racist ideas. With a history of persecution spanning well over three millennia, antisemitism is no laughing matter. Humor should never come at the expense of someone’s identity or their sense of safety.

It’s never been about politics. It isn’t about Israel. It’s about basic human dignity. We reject any form of hate, whether masked as activism or just a joke. Antisemitism is antisemitism, no matter how it’s packaged. And we believe Branson must continue to stand against it, loudly, clearly and always.

To our fellow students: You have power — in the way you speak, the way you joke and the way you respect your peers, your teachers, your school and your community. We urge you to use that power to make Branson a place where every student feels safe, seen and valued.