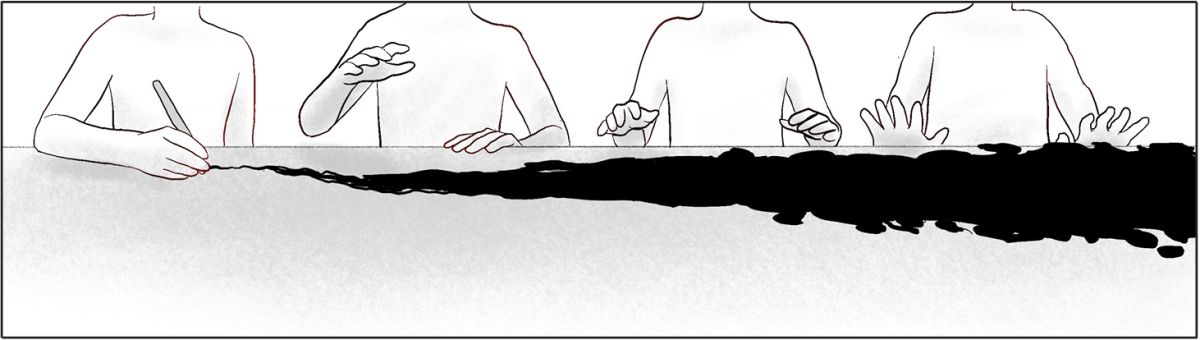

The average person can handwrite 13 words each minute, according to TCTEC Innovation, but can type 40 words per minute, according to TypingPal. That’s more than three times faster behind the keyboard than with a writing utensil.

Despite this clear inefficiency, many Branson students must now handwrite both the first draft of essays and in-class assignments in their English classes. With this change, students craft their work more slowly and cover less ground, which is especially challenging during 70-minute in-class writing sessions. With less time to edit and more in-the-moment pressure, the quality of writing suffers.

However, the English Department argues that handwriting has two main benefits that outweigh its slower pace. First, it prevents the use of AI tools, preserving the student’s original voice. Second, it emphasizes the process of writing rather than the finished product.

However, as a sophomore student who just finished my first English essay under this guideline, I believe handwriting causes too many inefficiencies to justify these benefits. It moves us backwards, requiring us to use outdated methods, rather than forwards, where we can learn to responsibly use digital tools that are prevalent in the real world.

With these arguments on the table, the English Department is understandably grappling with a new reality that is complex. Cheating, especially the use of AI, shouldn’t be something that English teachers have to deal with, especially because they grade dozens of papers at once for freshman and sophomore classes. Consequently, I imagine it would be disheartening to realize an essay you’ve graded was written by a robot, not a student. From this point of view, I understand the motivation to move away from screens and prevent AI usage.

Nevertheless, I don’t think handwriting can or will eliminate cheating and the use of generative AI. While you can’t open a ChatGPT browser in your Green Book and ask it to write your essay, there are other ways to bend and break the rules. For example, my English class switched to typing after our first draft: We edited and wrote introductions and conclusions on a Google Document. Within these time periods, a student could easily ask ChatGPT for help in smaller ways, like grading their essay or suggesting how the paper can improve, among other things. In short, while switching the first draft to handwriting does prevent a total essay overhaul with AI, it still leaves room for smaller robotic edits to occur that take away a student’s authentic voice in their writing.

This handwriting shift also intensifies the finished product mindset among the student body rather than highlighting the process of writing as the English Department intends. The finished product mindset is this idea that a student is focused more on how their writing looks at the very end. On the flip side, the process-based mindset highlights a learner’s emphasis on the multiple steps they took to draft and polish their essay, which is what the English Department promotes with handwriting.

However, with this emphasis on handwriting, most English teachers now grade students on three drafts: a first, second, and final draft. This grading change moves the writing focus away from the process because students must now worry about multiple finished products that meet teachers’ expectations, not just one. While this may prevent extreme procrastination, it also adds stress in the early stages of writing that highlights a finished product mindset through extra, unnecessary grades.

This move to limit the use of artificial intelligence raises a larger question of trust between students and teachers and threatens Branson’s tight-knit community. For example, The English teachers’ scattered incorporation of handwriting into their classes suggests they may question students’ commitment to produce authentic work, which, I’ll concede, is probably a fault of the students. However, the English teachers’ individual decisions about adding handwriting to their own curricula avoids student consultation and goes against the recommendations in Branson’s “Student and Family Handbook.”

On page 10, this handbook highlights the importance of communication between teachers and students: “a community with [a willingness to learn] at its center must perpetually commit to authentic communication to facilitate genuine learning…both as students and as listeners.” By addressing the whole community, the handbook emphasizes that all Branson members should learn from, listen to, and collaborate with one another. However, by incorporating handwriting rules at their own discretion, the English teachers are missing a crucial step of working with the student body to make decisions that “facilitate genuine learning” in their respective classes.

In conclusion, the implementation of handwriting in the English essay drafting process doesn’t eliminate the use of generative AI, intensifies stress and the finished product mindset and, if not properly addressed, has the potential to weaken trust between students and teachers and harm the Branson community. It’s time to rethink and rewrite this handwriting movement together.